Selected stories about our lab

Concussion & Brain Injury Prevention | Discovery Files Podcast

Concussion Technology in Sports

Padded Helmet Cover Shows Little Protection For Football Players

Padded Helmet Cover Shows Little Protection For Football Players

Football players particularly are prone to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a type of cognitive and mental decline caused by the head pounding they repeatedly receive on the field. To protect players, sports equipment companies are constantly improving helmets. A new product similar to the padded cover Camarillo used to wear is on the market now; called the Guardian Cap, it’s in vogue from high school fields to pro stadiums.

Football Seeks its Holy Grail.

Football Seeks its Holy Grail.

At Stanford, David Camarillo chases the dream of a helmet that can prevent brain disease related to playing football.

When Helmet Safety Meets Capitalism

When Helmet Safety Meets Capitalism

With attention and money increasingly directed toward player safety, SI surveyed equipment insiders and medical outsiders about the growing helmet industry. And the picture they paint, of a destined-to-be-unsafe world where marketing can cloud the science, is concerning.

Damage Control

Damage Control

As public concern intensifies, Stanford bioengineers and clinicians join forces in a drive to understand and prevent concussions.

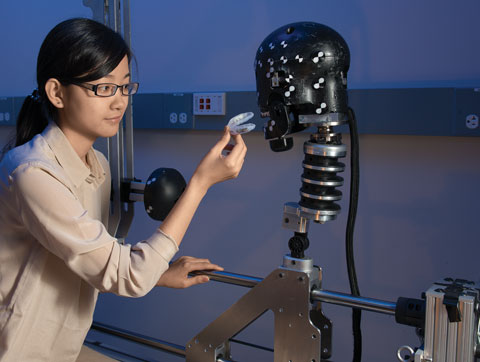

Stanford investigators are at the forefront of concussion research, and they are using Stanford athletic fields as their laboratories. Partnering with teams from football to volleyball, they are tackling such fundamental questions as: What are the biomechanical forces that cause concussions, and how can we prevent them? What happens in the brain during and after a concussion? How can we objectively diagnose and monitor concussions?

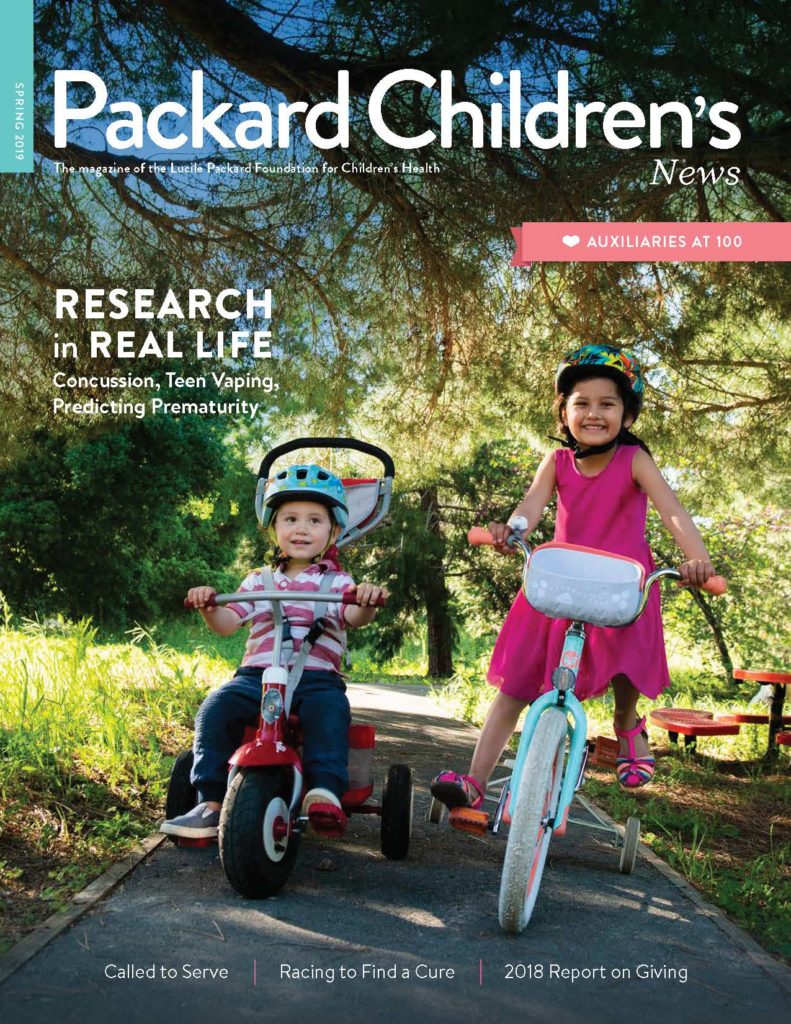

Protecting Precious Heads

Concussion experts team up to turn science into safer helmets.

“Ro-Ro, don’t forget your helmet!” calls David Camarillo, PhD, as his 4-year-old daughter, Rosie, jumps on her little turquoise bike. The training wheels wobble as she pedals away.

Parents give this same reminder to their children every day, but coming from Camarillo it has even greater significance. For the past seven years, he has studied concussions, an issue that affects approximately 2 million children each year in the United States.

What Happened Within This Player’s Skull

What Happened Within This Player’s Skull

The mouth guard that was used was developed by the bioengineer David Camarillo and his team at the Cam Lab at Stanford. Camarillo and others have speculated that the most damaging blows are those that cause the head to snap quickly from ear to ear, like the one shown above, or those that cause a violent rotation or twisting of the head through a glancing blow. “The brain’s wiring, essentially, is all running from left to right, not front to back,” Camarillo said, referring to the primary wiring that connects the brain’s hemispheres. “So the direction you are struck can have a very different effect within the brain. In football, the presence of the face mask can make that sort of twisting even more extreme.”

Reinventing The Football Helmet: Is Improving The Technology The Answer?

Reinventing The Football Helmet: Is Improving The Technology The Answer?

The NFL announced last week it will invest $100 million to advance concussion research. Rachel Martin asks David Camarillo, who leads a Stanford University lab dedicated to inventing such equipment.

VICIS looking to make its mark with helmets in NFL

VICIS looking to make its mark with helmets in NFL

CEO and co-founder of VICIS, INC Dave Marver and Stanford assistant professor of bioengineering David Camarillo join OTL to discuss helmets in the NFL.

The future of football equipment? Measuring a hit’s impact on the brain, not just the helmet

The future of football equipment? Measuring a hit’s impact on the brain, not just the helmet

The unchartered business territory is inside the skull, and the product that can accurately monitor head impact forces and concussion risk would be marketable to football players, sure, but also soccer players and rugby players, and even the military. But manufacturers have yet to crack the code for such a product.

“It’s a little bit of the wild west right now,” said David Camarillo, assistant professor of bioengineering at Stanford. His lab is working on a force-measurement mouth guard. “Most of these businesses, as far as I can tell, it’s been kind of a grave yard. A lot of these businesses don’t make it.”

Airbag bike helmets may be safer than conventional foam versions

Airbag bike helmets may be safer than conventional foam versions

Bicycle helmets that utilize airbag technology instead of conventional hard foam may offer five times more protection against brain injuries, according to Stanford University researchers.

The Bioengineer Trying to Predict and Prevent Concussions

The Bioengineer Trying to Predict and Prevent Concussions

Bioengineer David Camarillo has suffered his fair share of blows to the head. The worst happened two years ago while biking across a San Francisco intersection. The concussion he sustained left him mentally foggy, unable to read his watch or calculate tips. He developed PTSD. He hasn’t biked since.

Stanford Researchers Measure Impact of Football Concussions

Stanford Researchers Measure Impact of Football Concussions

Preventing concussions in football requires first knowing what types of hits cause them. Stanford scientists have developed technologies that will help unlock that mystery.

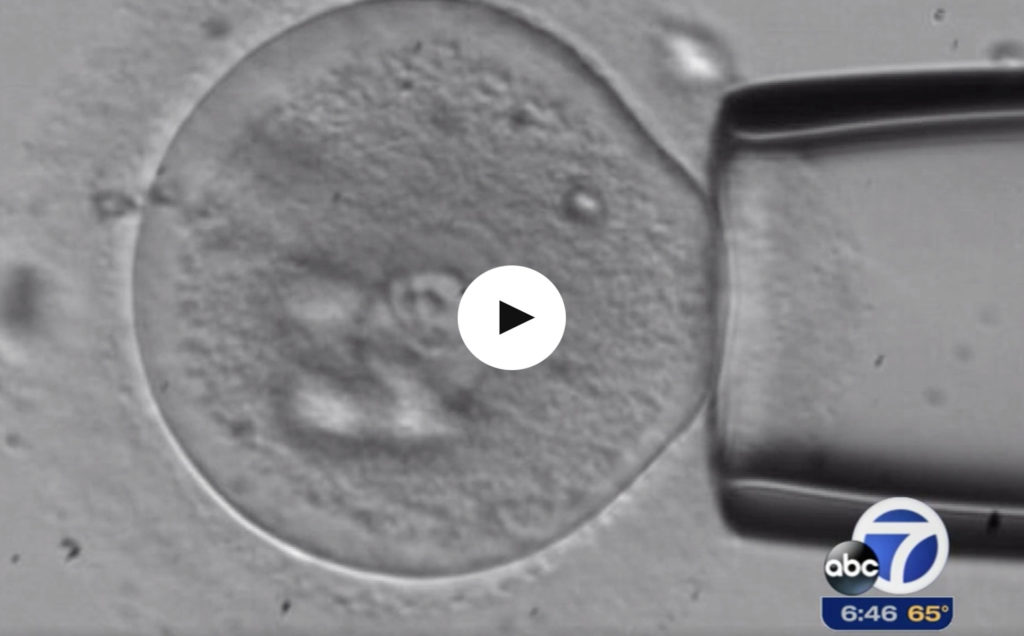

Stanford Tests for Squishy Embryos

Stanford Tests for Squishy Embryos

What can squishiness tell you about newly fertilized egg? It turns out, a lot. Maybe even the odds of whether the embryo will grow and develop in the mother’s womb. In the Camarillo bioengineering lab at Stanford, engineers measure impacts both big and small. And that ability can help in research as far ranging as preventing concussions to improving in vitro fertilization.

More news

Stanford researchers outline the role of a deep brain structure in concussion

Concussion researchers study head motion in high school football hits

Concussion researchers study head motion in high school football hits

Three Bay Area high school football teams have been outfitted with mouthguards that measure head motion. Stanford scientists hope to use the data to better understand what causes concussions.

Scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine are collaborating with football teams at three Bay Area high schools to understand how hits to the head cause concussions in young players. Continue Reading

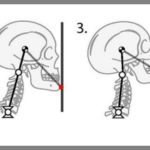

Study shows how head, neck positioning affects concussion risk

The way the head and neck are positioned during a head-on impact may significantly affect the risk of concussion, but tensed up neck muscles seem to offer far less protection, Stanford researchers found.

If you’re about to run headfirst into something, your reflex might be to tense your neck and stabilize your noggin. But according to a new study by researchers at Stanford, that may not be the best way to stave off a concussion. Instead, the findings suggest that your head’s position is more important than whether you are tensing your neck. Continue Reading

Researcher probe the complex nature of concussions

Researcher probe the complex nature of concussions

Concussion is a major public health problem, but not much is known about the impacts that cause concussion or how to prevent them. A new study suggests that the problem is more complicated than previously thought.

It seems simple enough: Taking a hard hit to the head can give you a concussion. But in most cases, the connection is anything but simple, according to a new study led by researchers at Stanford University. Continue Reading

Stanford Engineers Explore Mysteries of Brain Injuries

Stanford Engineers Explore Mysteries of Brain Injuries

Most football fans have seen a player taken from the field after a shot to the head as an announcer says, “He really got his bell rung.” That makes it sound like his brain was clanging back and forth in his skull like the clapper in a bell. Continue Reading

Taube gift to launch youth addiction, children’s concussion initiatives

Two gifts totaling $14.5 million from Tad and Dianne Taube will fund Stanford efforts to understand, treat and prevent concussion and addiction in children and teens.

Tad and Dianne Taube of Taube Philanthropies have made two gifts totaling $14.5 million to the School of Medicine and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford to address addiction and concussions — two of the most significant issues affecting the health and well-being of children and adolescents. Continue Reading

Air-bag helmet could reduce impact of head in bike crashes

Air-bag helmet could reduce impact of head in bike crashes

Drop tests from as high as 2 meters show that an air-bag helmet may reduce impact by as much as sixfold compared to traditional bike helmets.

David Camarillo knows all too well that bicycling is the leading cause of sports- and activity-related concussion and brain injury in the United States. He’s had two concussions as the result of bicycling accidents. While he doesn’t doubt that wearing a helmet is better than no helmet at all, Camarillo thinks that traditional helmets don’t protect riders as well as they could. Continue Reading

Researchers measure concussion forces in greatest detail yet

Researchers measure concussion forces in greatest detail yet

Research led by David Camarillo could eventually lead to better concussion detection and prevention.

More than 40 million people worldwide suffer from concussions each year, but scientists are just beginning to understand the traumatic forces that cause the injury. Continue Reading

Damage Control

Damage Control

In the fall of her freshman year, basketball standout Toni Kokenis was knocked to the floor during a layup, slid under the basket and—in a freak accident—hit her head on a photographer’s camera. She shook it off and continued to play. But she awoke the next morning in a fog. She was barely able to get out of bed to see the team trainer, who diagnosed a concussion, her second. (The first happened in high school.) The Stanford starting guard recovered in a few weeks and went on to play on two Final Four teams, in 2011 and 2012. Continue Reading

Even Small Football Impacts Can Ring the Head Like a Bell

Even Small Football Impacts Can Ring the Head Like a Bell

When it comes to head impacts, it’s not just the hard-hitting blows that you should worry about. A new study finds that even small hits can cause the brain to vibrate dramatically inside the skull.

Head injuries in sports have come into the spotlight in recent years. Brain trauma has been implicated in the suicides and domestic violence cases of several NFL players, and even the deaths of several high school athletes. As a result, parents and fans are becoming increasingly sensitive to issues of safety. Continue Reading

Most sensors designed to measure head impacts in sports produce inaccurate data, Stanford bioengineers find

As scientists zero in on the skull motions that can cause concussions, David Camarillo’s lab has found that many commercially available sensors worn by athletes to gather this data are prone to significant error.

Amid growing concern over sports-related concussions, some athletes are beginning to wear head-mounted sensors that gauge the speed and force of impacts they sustain during competition. Scientists are still working on identifying baseline parameters for injury, but research suggests that certain skull motions can contribute to concussions, and constant in-game monitoring of those motions promises to help limit injuries. Continue Reading

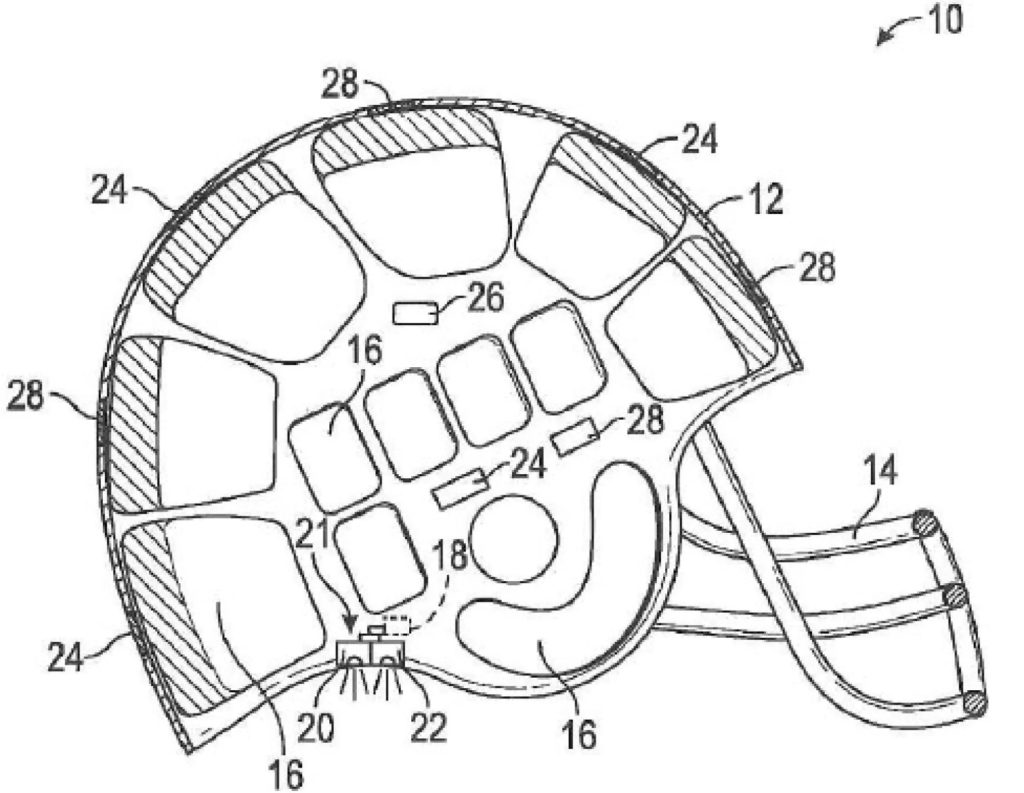

Stanford research suggests football helmet tests may not account for concussion-prone actions

Stanford research suggests football helmet tests may not account for concussion-prone actions

Mounting evidence suggests that concussions in football are caused by the sudden rotation of the skull. David Camarillo’s lab at Stanford has evidence that suggests current football helmet tests don’t account for these movements.

When modern football helmets were introduced, they all but eliminated traumatic skull fractures caused by blunt force impacts. Mounting evidence, however, suggests that concussions are caused by a different type of head motion, namely brain and skull rotation. Continue Reading